A gedankenexperiment on vaccination

tl;dr. I’m describing a thought experiment that hopefully helps to convince people to get vaccinated despite feeling uncertain about some aspects of COVID-19.

Motivation

Unfortunately, some in my family still refuse to get vaccinated against COVID-19 for no good reasons despite the fourth wave rolling over Germany. This saddens me. I haven’t given up on changing their minds yet but discussing the issue is extremely difficult. On one hand, it has turned into a highly emotional topic. On the other hand, many people seem to really struggle with reasoning in the presence of uncertainty. And there definitely still is plenty of uncertainty around COVID-19 and the vaccines against it.

In my experience, people who are skeptic about vaccines tend to derail discussions with lots of one-sided objections like “but the vaccine might be more dangerous than the disease” or “the vaccine might be more problematic for me than for the rest of the population”. Even if that might be the case, it might also be the other way around. Having this sort of conversation where a lot of things might be but neither person knows enough to convince the other can be incredibly arduous.

The gedankenexperiment1 I’ve designed to aid my attempts to influence my family members reduces the number of facts we actually need to know to a minimum and embraces that there is plenty we don’t know. Although there are vast amounts of evidence in the specific case of COVID-19 that the vaccines against it are safe and highly effective, if we can ignore this evidence and still come to the conclusion that getting vaccinated is the right thing to do, we avoid getting bogged down in a discussion about the validity of the evidence. One could call this approach evidence frugality.

Gedankenexperiment

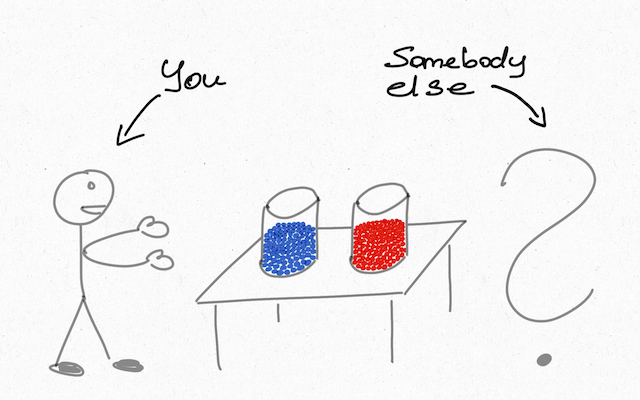

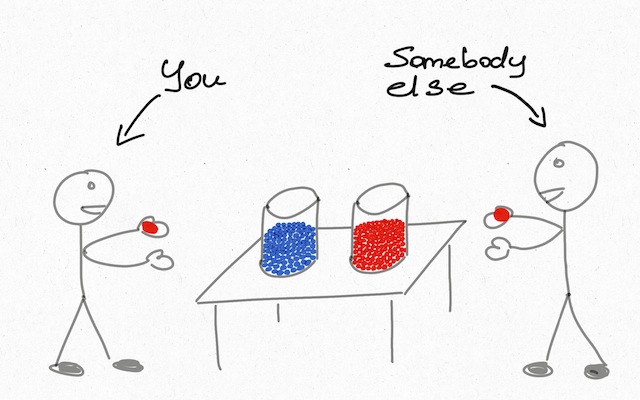

Imagine you’re standing at a table with two jars full of pills on it; the left jar contains indistinguishable blue pills and the right jar contains indistinguishable red pills. You have to pick one of the two jars and take a pill from it.2 Once you’ve taken your pill, some other person will have to take a pill as well. The exact options that person will have depend on what color you chose. You don’t know who that person is, it could be a dear friend or a complete stranger.

You also don’t know much about the pills. The only thing you know is that some of them are poisonous to some degree and all the others are placebos without any effect on you or anybody else. However, you don’t know how poisonous the poison pills are, they could be deadly or only upset your stomach, and you also don’t know how big the proportion of poison pills in either jar is. In other words, taking a pill entails some risk without any potential reward and it’s completely unclear which jar is more dangerous. Still, you have to decide if you take a blue pill or a red pill.

Depending on how you decide, the other person has to take a pill as well. If you take a red pill, the other person has to take a red pill too, immediately after you.

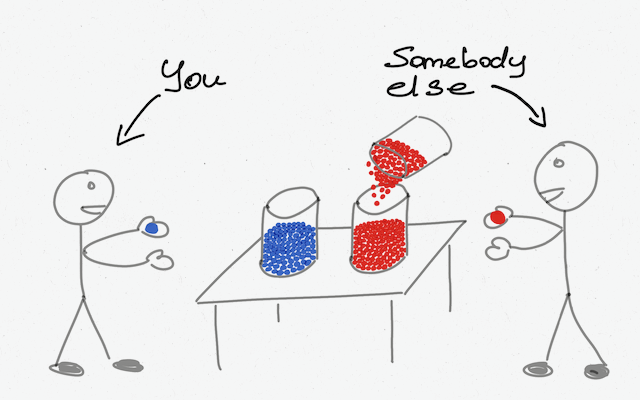

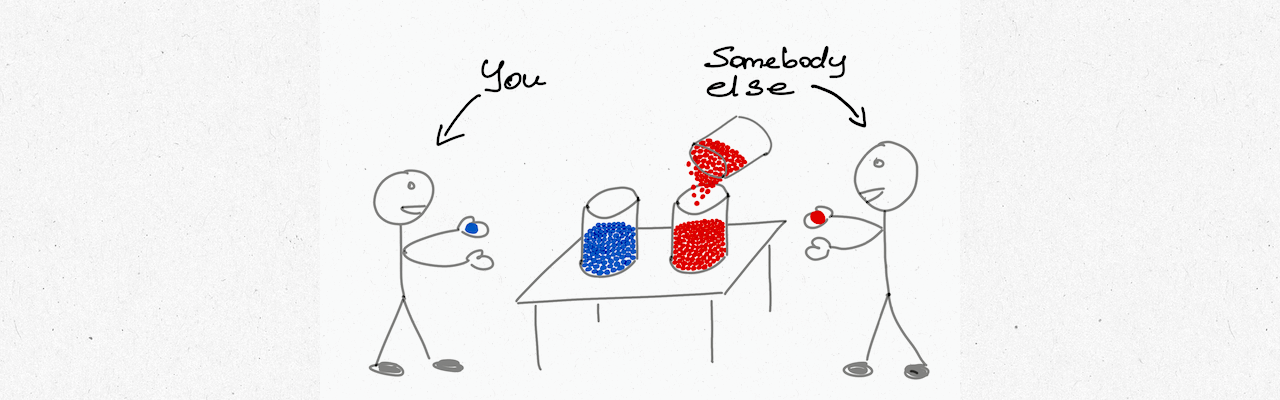

If you take a blue pill, the other person still has to take a red pill, but not immediately. Before they do so, the jar with red pills is topped up with an unknown number of new red pills. These new pills look exactly the same as the old pills already in the jar but all of them are non-poisonous placebos. The jar is then properly stirred and shaken. Once the old and new red pills are completely intermingled, the other person has to pick a red pill take it.

Given all that information but nothing else, how do you decide:

Do you take a blue pill or a red pill?

Interpretation

I’m pretty convinced that everybody who has the slightest understanding of basic math and is not a sadist would take a blue pill if presented with this situation. The reasoning is pretty simple:

- For themselves it doesn’t make a difference if they take a blue pill or a red pill since they simply don’t know which one is less dangerous for them.

- If they take a blue pill, the risk for the other person to get a poison pill is lower than if they took a red pill.

In other words, if they take a blue pill they make the situation for the other person better without making their own situation worse. No matter how egoistic they are, there simply is no incentive for them to take a red pill. Taking a red pill nevertheless would seem quite sadistic to me.

One might be tempted to interpret picking a blue or a red pill to symbolize getting or rejecting the vaccine, respectively. I’m not convinced such an interpretation is necessary or helpful. If anything, it opens the door for pointless discussions about how well the experiment represents reality. And why is the other person is allowed to take a red pill when oneself is supposed to pick a blue pill?

I would try to leave this door closed and instead leave the interpretation of the gedankenexperiment at a more abstract level: When confronted with two somewhat dangerous choices A and B and one doesn’t know whether A or B is more dangerous for oneself but choosing A is less dangerous for others, then choosing A is the right thing to do.

The beauty of such an argument is that the first half of the precondition is about not knowing and hence reasoning along these lines cannot be rejected by a counterargument of the form “but I/we don’t know whether…” That’s the whole point of the gedankenexperiment. And everybody who decides that a blue pill should be taken for the reasons outlined above pretty much confirms that such a line of arguing is acceptable for them.

Conclusion

Let’s come back to COVID-19 and apply the argument to the disease and the vaccines against it. Assume choice A is to get the vaccine and choice B is to not get it. Anybody who wants to reject the argument for these specific choices, would need to argue for one of two points:3

- They know that getting the vaccine is more dangerous for them than not getting it.

- Getting the vaccine does not reduce the danger for others at all.

Given the data we currently have overwhelmingly shows that the vaccines are safe and effective, arguing for either of these two points seems quite vain.4 In fact, the people I’ve argued with so far didn’t even try to do so.

Their strategy rather appeared to be to derail the discussion with plenty of one-sided objections like “the vaccine might be more dangerous than the disease (in the long term)”. Yes, that might be, but it might also be the other way around, we simply don’t know for sure. And what should do we do if we don’t know? We should do what’s best for others and get the vaccine!

-

German is my native language and I’m always quite amused about German words that have made it into the English language unchanged. Maybe it’s a bit of schadenfreude that English speakers occasionally have to deal with a word as long as a freight train, too. Thus, I’ll stick with the zeitgeist here and refrain from translating the original “gedankenexperiment” into the potentially more common “thought experiment”.

↩

↩ -

Refusing to take a pill is not an option because we’re in a gedankenexperiment. In real live, the action represented by taking a blue pill could be doing something and taking a red pill could stand for not doing that same thing. Hence, not taking a pill would not be an option, except for people who found a way around the law of the excluded middle. ↩

-

Technically, they could also reject the argument in the way it is presented by arguing that not getting the vaccine is more dangerous for them than getting it. I would happily take a discussion going down that route every single day. ↩

-

I’m aware that there are people who have a medical condition that makes the vaccine an actual danger to them but they are very few. Those are not the people I’m trying to convince to get vaccinated anyway. ↩

Comments